Black History Month lecture examines American quest for justice

UCLA professor, a frequent commentator on National Public Radio, discusses violence against black women and the struggle for justice for all races.

Seeking justice has been at the core of the American experience from the very beginning.

It led to freedom from English tyranny in 1776, and today it leads the charge for racial equality.

For Brenda Stevenson, that constant challenge has become as American as apple pie.

“The powerful rally cry of ‘No justice, no peace’ isn’t so different from ‘No taxation without representation’ or ‘Give me liberty or give me death’ – popularized refrains that led a generation of patriots to the founding of this great nation,” she said.

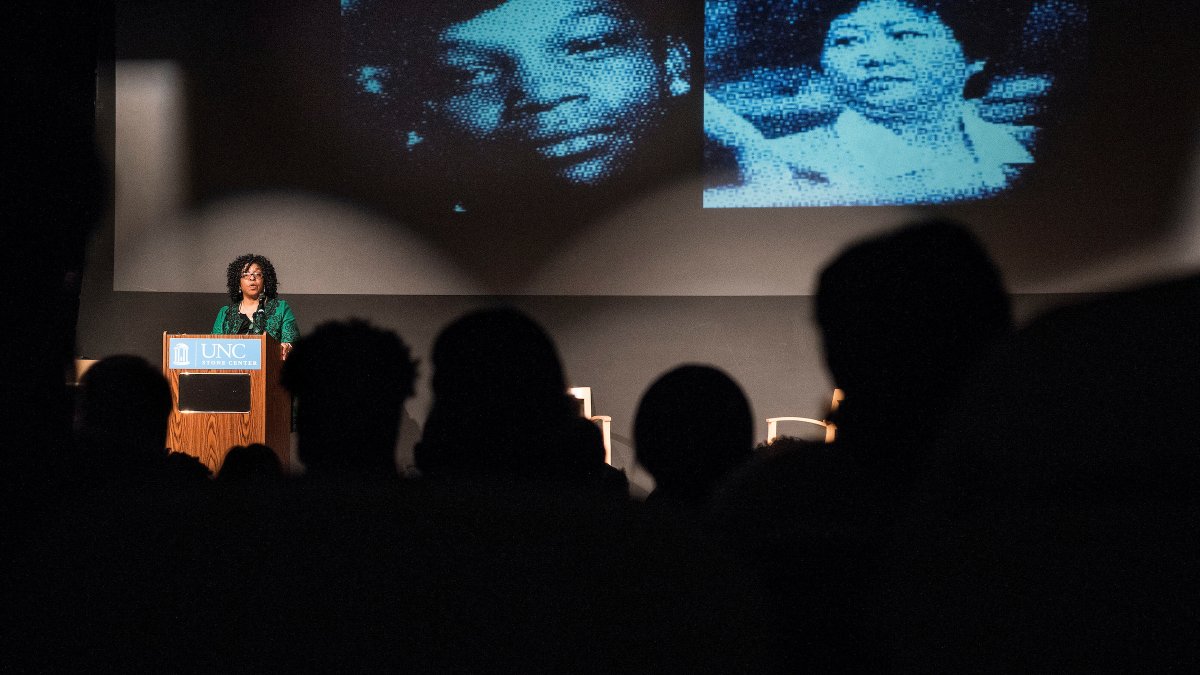

Stevenson, the Nickoll Family Distinguished Professor of History at UCLA and a fellow at Stanford University’s Center for Advanced Studies in Behavioral Sciences, discussed the violence against black women and the struggle for justice for all races in her talk “When Do Black Female Lives Matter? Contested Assaults, Murders and American Race Riots.”

Her presentation was the keynote address of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s 13th annual African-American History Month Lecture at the Sonja Haynes Stone Center for Black Culture and History.

Chancellor Carol L. Folt introduced Stevenson and shared that the two-hour lecture was a chance to learn from history and understand how it can be used to shape the future.

“There are times in history where we turn to stories and the telling of those stories to learn, to teach and to inspire,” she said. “Those are the times that we use our learning from the past to affect the changes that we want to see today. The telling and the sharing of history are vital to advancing diversity and inclusion.”

Held Feb. 8, the event was hosted by the Offices of the Chancellor and Provost; the College of Arts and Sciences and its departments of communications, music, history and African and African American diaspora studies; the Carolina Women’s Center; the Center for the Study of the American South; Diversity and Multicultural Affairs; Delta Sigma Theta; and the Stone Center.

The lecture was just one of Carolina’s many Black History Month events. Throughout February, University organizations are hosting lectures, panels and other events to celebrate the observance.

Stevenson, an author and frequent commentator on National Public Radio, is an expert on African-American history, black women and families and race relations.

She is also the recipient of the Ida B. Wells Award for Courage in Journalism and the Southern Historical Association’s John W. Blassingame Award, given for distinguished scholarship and mentorship in African-American history.

Lecturing on the case of Latasha Harlins – a 15-year-old black girl who was killed by Korean-American female storeowner Soon Ja Du in 1991 – Stevenson discussed how the lenient sentencing of Du ignited the 1992 Los Angeles riots.

“The shooting was devastating but was also profoundly different from the usual violent scenario across racial lines that typically garners public exposure,” she said. “The people involved, Soon Ja Du and Latasha Harlins, were female, not male. Du was Korean, not white. She was a mother, wife and shopkeeper. Not a policeman, deputy sheriff, security guard or homegrown terrorists with a white sheet over her head.”

When the judge sentenced Du to five years probation, 400 hours of community service and paying for funeral expenses, the community took to the streets to protest the injustice.

The media’s attention to the case, Stevenson said, further exposed the vulnerability of the most defenseless group in the United States – the women and children of racially, culturally and politically marginalized communities.

But that vulnerability had been a trend for decades prior, with injustices toward black women and children sparking tensions. It’s a vicious cycle, Stevenson said, that falls on all of society to break.

“It’s something that we have to continue to voice, continue to write about, continue to march and protest about and sing about and write poems about,” she said. “These are things that we really have to do. It’s everyone’s responsibility. It’s not just black women’s responsibilities. It’s not just black people’s responsibilities. It’s everybody’s responsibility to do that — everyone who lives on Earth to do that.”