Physics students choose their own adventure

When the University transitioned to remote learning, physics lab instructors created a digital format where students can still make creative choices or even mistakes.

When the COVID-19 outbreak prevented physics students from attending their labs in person, their instructors brought the labs to them. Several physics labs transitioned last week to an online “choose your own adventure” style, where students are encouraged to ask questions and make mistakes as they would in a physical lab.

“We’re giving students the opportunity to interact and make choices as they would if they had lab equipment in front of them,” said Jennifer Weinberg-Wolf, teaching assistant professor. “They can’t physically manipulate things, but we tried to give students different pathways they can follow through the experiment.”

In a typical physics lab, the students are introduced to a topic in lecture and then dive into that topic in more detail in lab sections where they conduct experiments and other activities.

According to Duane Deardorff, director of undergraduate laboratories, these hands-on learning activities are essential to the student experience in physics courses.

“In our advanced courses, students rotate through different stations and spend two or three hours doing an experiment with specialized equipment, which students would not have access to on their own,” said Deardorff. “This is their chance to practice the scientific method.”

The “choose your own adventure” online labs were designed to include the experimental approach needed for students to still learn how to use the scientific method and practical skills, such as utilizing the specialized lab equipment.

Weinberg-Wolf is credited by her colleagues as the first instructor to suggest the approach.

“I presented it first to other faculty when we were discussing different ways to teach remotely,” said Weinberg-Wolf. “I was focused on how we could use the equipment to replicate what students would normally see in lab.”

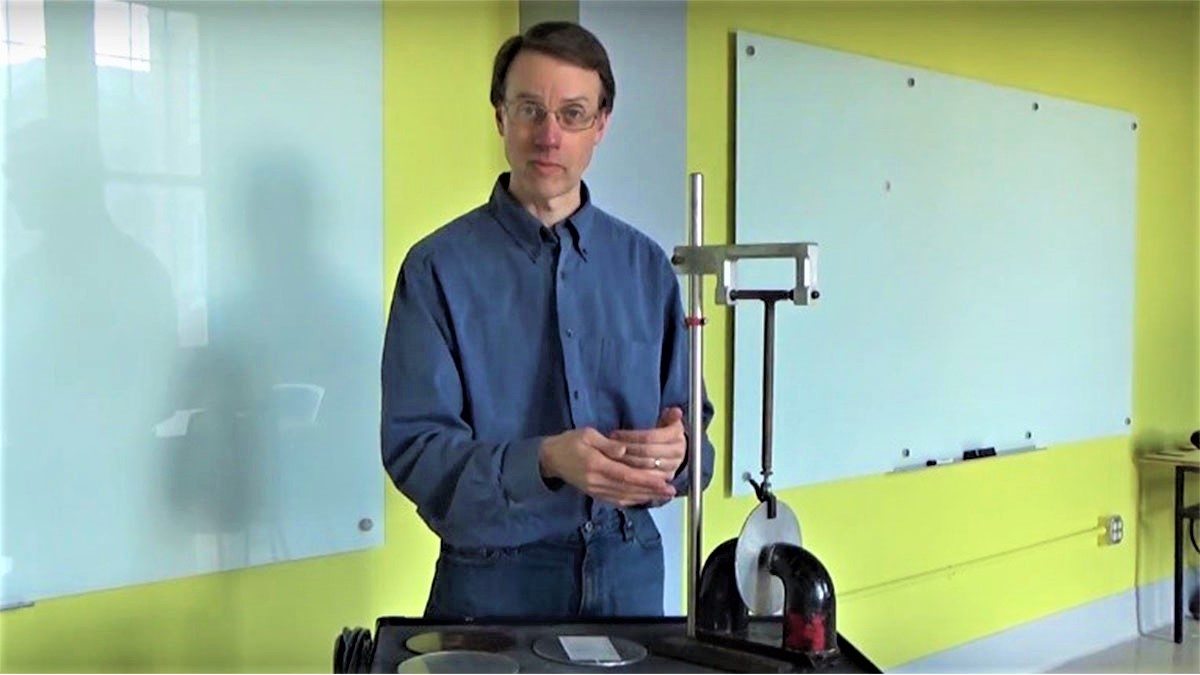

The interactive online labs combine a number of digital components: images of lab equipment and measurements, videos of instructors conducting experiments and breakout sessions with their peers.

Students first “choose their own adventure” by picking which in a series of images represents the correct setup for the lab experiment. Students use digital simulations to manipulate instruments on their screen so they can still replicate the process of taking measurements. They then analyze data sets and differentiate which constitute “good” data sets and which will end in a failed experiment.

Most importantly, lab instructors can allow students to make mistakes and help them understand where they went wrong.

Lab instructors also created videos of themselves conducting the experiments in steps, so the students understand how the data was collected.

“I created a series of YouTube videos of me or my co-instructor doing the experiment in the lab, focusing on our hands and how we’re using the lab equipment,” said Benjamin Levy, a course instructor and graduate student in the physics department. “I think that’s a big part of what makes an experiment effective and teaches the students how to conduct experiments – they have to see somebody holding the lab equipment in their hands, even if they can’t.”

The physics faculty also prioritized maintaining a collaborative approach when designing the “choose your own adventure” labs. Students still meet in groups to work through labs as usual, but their meeting rooms are now digital.

“In the first week of online learning, I gave them some options to choose from and sent each lab group to separate digital rooms and they discussed and figured out how to solve a problem,” said Weinberg-Wolf. “The groups came up with five or six different solutions, so the students are still working together and being creative.”

Physics instructors found that the switch to remote learning also provided quieter students with a new chance to participate.

“I have noticed that students who haven’t come to office hours in the past have started sending more messages with questions and requests for meetings, so it seems learning remotely has lowered a barrier for students who were intimidated by asking a question in front of the class or attending office hours in person,” said Levy.

Above all, the physics faculty are focused on providing their students with the tools they need to succeed.

“We’ve made some adjustments to make sure everyone has access to what they need – we’re allowing students to attend different sessions that fit their new schedules best or when they have internet access,” said Deardorff. “Our department is still working to find the best method for teaching remotely, and we’ll continue to find the best solutions for our students. This was, and will continue to be, a collaborative effort.”